test heading</h2[From the Drawing Board of Gene Yang]

I got back from Angoulême two weeks ago and my brain is

still reeling from the experience. For

those of you who don’t know, the name “Angoulême” refers to two things:

- A small town in France,

about two hours’ train-ride south of Paris - The Western world’s largest comic book festival (or

“convention,” as we call ‘em here in the States) which takes place annually in

that town

Dargaud, the French publisher of American Born Chinese,

invited me across the pond as their guest, and I got to spend four days rubbing

elbows with many of the most brilliant cartoonists in the world. Graphic novels from practically every

comics-reading culture were on display.

On my first afternoon there, I sat down at my publisher’s

booth to do a signing. I started off

signing books just like I do in America: the reader’s name in all caps, a happy little

message, my loopy signature, and a quick doodle of the Monkey King’s head to

prove I’m the guy who did the book. About five books in, I began noticing that the readers were all walking

away with frowns. Had I spelled their

names wrong? Did I smudge the drawing

with my hand? Was it a French custom

that I wasn’t familiar with, frowning at the sight of a newly signed book?

Then I took a good look at what the French cartoonists

around me were doing. The one on my

right was crosshatching a carefully rendered fight scene on a jacket flap,

while the one on my left was finishing up a watercolor portrait of her

protagonist on the bottom half of a title page. I realized my little monkey heads just weren’t cutting it. French comic book readers expect sketches

that are works of art rather than just sketches, and French creators are more

than willing to oblige. In an hour, a

cartoonist would sign maybe eight books tops, and everyone was happy about

it. The readers didn’t complain about

the wait, and the cartoonists didn’t complain about cramped drawing hands. I had to step up my game.

The elaborate sketches were indicative of a general atmosphere

that pervaded the entire show. The

emphasis of Angoulême wasn’t on autograph collections or limited edition toys

or blockbuster movies or skimpy costumes. The emphasis was on the art of comics. Everything else took a backseat, and everyone understood this. Displays of original comic book art adorned

the halls, just as they do at American conventions, only in Angoulême these

displays weren’t afterthoughts — they were the main attractions.

Now, don’t get me wrong. I love the zaniness of American comic book conventions. I love watching Jack from Jack-in-the-Box and

the King from Burger King engage in a light saber duel before a rapt audience

of classic Nintendo characters. I love

hearing Klingons shout Klingon jokes to other Klingons, and then laugh hearty

Klingon laughs. I even love bumping into

overweight Optimus Prime as we both search for those elusive issues of The

Warriors of Plasm in an endless sea of dollar bins. But to be at a festival where comic books are

seen — not just by the professionals, but by pretty much everyone in

attendance — as an art form in every sense of the word “art”… this was as

close to Hicksville (a geeky way of saying

“comic book heaven”) as I’m ever going to get.

The draftsmanship of the French creators certainly reflected

this attention to craft. I watched in

amazement as fully-formed scenes spilled out from their pens without a single

pencil sketch line to guide them. I met

cartoonists who had mastered a half dozen media to tell stories in a half dozen

genres. The panels that make up their graphic novels resemble small,

carefully-composed paintings, with conscious thought evident behind every brush

stroke and color. There is much that we

Americans can learn from the French.

Of course, the reverse is also true. After all, Will Eisner and Charles Shultz

were Americans.

And maybe that’s why I feel so lucky to be working in comics

right now. The three major comics

traditions of the world — Japanese, French/Belgian, and American – are in the

midst of a Great Cross-Pollination. More

often than not, cartoonists today can trace their influences around the globe,

to other cartoonists with whom they’d barely be able to sustain a verbal

conversation. And yet, through this

medium that combines the universal communication of pictures with the specific

communication of words, we’ve found a profound way to share with one another.

It’s an exciting time to be in comics. As a friend remarked to me recently, it’s

like being at the birth of rock-and-roll.

Angoulême

the town

Angoulême

the comic book festival

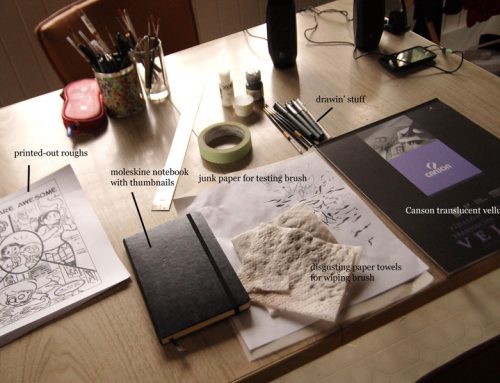

Me trying

to step up my game

Lewis

Trondheim, me, and Christophe Blain

[UP NEXT WEEK: TEDDY KRISTIANSEN]

Now that’s just awesome. The various responses (and suggestions & compliments) to ABC must have Gene flying on Cloud 9!

I remember when I attended the Comics Salon in Erlangen in 1994. I was surprised to find everyone doing artwork, so I rushed out and bought some art paper. I have two wonderful self portraits from Scott McCloud, and a fully rendered “sketch” of Scrooge McDuck from “Legends of the Lost Library”. It’s happening again this Spring, and it’s like Angouleme, but much less hectic. (At least it was in 1994.)

it wasn’t amazing only for you, due to the fact that you are not an european.it was amazing and unique experience for a greek also. Even if I am not a comic artist, but a loyal comic reader I couldn’t stop runnning from one excibition to another in order to see everything.French are the best at this kind of festivals. Totally organised.

next station, who knows, maybe San Diego

it’s awesome you made it to Hicksville, my friend.

It’s like we’re living in a comic-book “melting pot” right now — creators are coming up with new styles and ideas by sampling other culture’s comic traditions. There’s bound to be some awkward experimentation coming from this, but there’s also bound to be a steady stream of AMAZING work from these creators.